Teaching and Learning at 31 Schools During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The different perspectives of teachers and students are highlighted in this study done by Jia Wang, Deborah La Torre, Linda Adreani, Lauren Kinnard, and Seth Leon at the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST) at UCLA

Nearly three years after schools in Los Angeles, and across the nation, closed down as COVID-19 spread across the globe, and as students begin to return to schools in somewhat normal fashion, researchers at the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST) at UCLA have published a new study, examining the experiences of K–12 students and teachers during the pandemic and offering initial insights into what happened with teaching and learning during these challenging times.

Jia Wang, an adjunct professor at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies and a senior research scientist at CRESST, and her research colleagues Deborah La Torre, Linda Adreani, and Seth Leon, examined the perspectives of teachers and students in their study, “Teaching and Learning at 31 Schools During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Students and teachers from schools in California, Connecticut, and Florida participated in the study.

Concerns over the impact on student learning are increasing amid worries of “learning loss,” by educators, policymakers and others. Wang, the principal investigator of the new CRESST study, says she really does not like calling what has occurred “learning loss.”

“I feel like this has been more a loss of learning opportunity,” says Wang. “Students have not had a normal, in-person learning experience for two-plus years. Their loss of typical learning opportunity during the pandemic led to their learning outcomes being reduced. With that said, I just can’t emphasize enough, 2020 and 2021 were not normal typical school years.”

The majority of the students surveyed reported that they learned as much as or more than before the pandemic, while about two-thirds of the teachers surveyed thought their students learned less.

La Torre and Wang underscore that it is important to remember that teachers and students are coming from different viewpoints. Students may be taking into account different things than teachers, and don’t always particularly know what they are supposed to accomplish during the school year, while teachers have clear ideas of what they think their students should be accomplishing and where their students should be in their learning trajectories. Besides, students may have evaluated their learning beyond the academic learning in core subject areas such as their newly developed technology proficiency.

THE PERSPECTIVE OF STUDENTS

During the pandemic, students attended school in a variety of formats or settings. A little more than one-third (37%) of students in the study attended school in-person, while 38% attended school online only. About a quarter (24%) of the students reported attending school in a hybrid mode where they had some in-person instruction and some online learning experiences within a given week.

The study found the majority of students had positive perceptions about their learning. More than one third said they learned about as much, while nearly a quarter said they learned more than before the pandemic.

Schools played an important role in supporting students by providing technology access, with 63 percent of in-person students and 69 percent of hybrid/online students reporting that their school gave or lent them a laptop, desktop computer or tablet to use for their homework and/or schoolwork. The survey found that having access to a laptop, desktop computer or tablet had a clear and positive effect on their experience. More than 60 percent of in-person students who reported having their own device (64.8%) or a device from school (61.6%) felt that they learned as much or more than before the pandemic.

Student participation in class time activities also seemed to matter. Among students who reported they used digital materials on a weekly basis or more often during the 2020–21 school year, 58 percent of in-person students had positive learning perceptions and had some experience working on digital textbooks, workbooks, or worksheets.

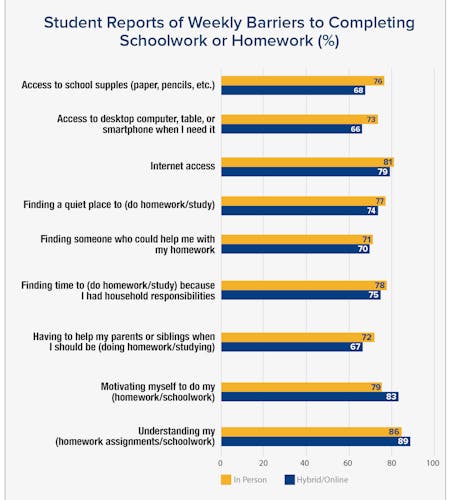

The survey makes clear however that a majority of students experienced barriers to learning on a weekly basis during the 2020–21 school year. For example, about 70 percent of in-person students reported issues with access to school supplies, such as paper or pencils, at least a few times per week, with more than 40 percent noting this was an everyday issue. And despite acknowledging efforts by schools to provide students with access to technology, large proportions of students said they had problems accessing a desktop computer, tablet or smartphone. About eight in ten students also said they had issues with internet access a few times to every day during a typical week.

Students also said they struggled to understand school work and homework assignments, and about 70 percent said they had difficulty finding someone to help them with their homework, or a quiet place to work on it.

But even as they encountered barriers, more than half of those students still felt they had learned about the same or more than before the pandemic.

“It may just be that sometimes students are just more resilient than we think that they’ll be,” La Torre said. The survey findings seem to support that idea. Students expressed positive views about learning and expectations for the future. More than three-quarters of students reported that learning new things and getting good grades are important, and agreed that doing well in school is important for their future. More than eight in ten students said they worked hard to do their best in their classes. About 95 percent of students said they expect to graduate from high school or attend college in the future.

“Even though it may not be a hundred percent based on reality, we were really happy to see students so positive about their experience,” Wang adds.

THE VIEW FROM TEACHERS

It is safe to say that teachers saw things differently from students. More than half of the in-person teachers (56.6%) and more than three-quarters of the hybrid/online teachers (75.2%) said their students learned less than they did prior to the pandemic.

“I think that the students were judging themselves for the most part, as being on par with where they thought they would be in their learning, or doing better than they thought they would be doing in their learning,” La Torre said. “The teachers though were, for the most part, feeling like their students were doing less than they had expected.

“We should also keep in mind that teachers are always gathering information, not just from the tests, but day-to-day while they’re in the lessons, the questions that they’re asking their students, how the students are responding, what the students are asking. There’s all this other information that they gather.”

The study examines whether teachers taught in-person, online or in some type of hybrid fashion; the structure, type and use of school time activities; their participation in and perceptions of professional development; their collaboration with other teachers; and the support they provided to students.

About 58 percent of teachers were teaching in a hybrid fashion, with 41 percent teaching in person.

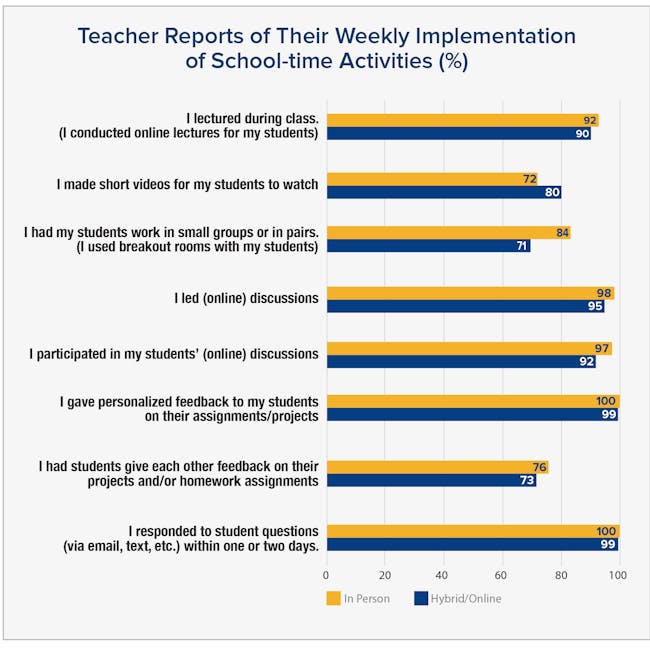

The responses of both groups of teachers, with some important exceptions, were fairly similar. Moderate to large percentages of teachers reported they used a range of the instruction techniques listed on the survey at least a few times to every day during a typical week. For example, more than 90 percent of teachers reported conducting lectures in person or online, and more than 70 percent said that they made short videos for their students to watch and that they created pre-recorded lessons or other digital materials for students. Somewhat larger proportions of the hybrid/online teachers reported using the different activities and, in some cases, used them more frequently.

The teachers also reported significant participation in professional. development activities. For example, more than half the teachers reported meeting with other teachers for ten or more hours to develop materials or activities or to work on instructional strategies, and nearly half said they participated in formal professional development sessions taught by a teacher, coach or administrator from their school. More than half of teachers said they spent ten or more hours attending professional development on using technology for teaching purposes or content area teaching.

The teachers had positive perceptions of their professional development. Among the highest-rated outcomes were learning how to use technology to improve instruction. Almost all hybrid/online teachers reported that they learned how to use technology to improve their instruction.

During the pandemic, teacher collaboration activities continued. For example, more than two-thirds of teachers reported that they had regular meetings with other teachers at their school or district, discussed ideas about how to improve student engagement during lessons or students’ social-emotional needs.

The majority of teachers, and more so among those teaching in person, expressed positive views of the support they had given to students. More than 80 percent agreed or strongly agreed that they motivated their students. Among those teaching in person, 83 percent said they provided effective instruction, and 73 percent of those teaching online said the same. Large majorities of both groups felt they had sufficient training and/or experience to integrate technology for effective teaching.

One concern was that less than half of the hybrid/online teachers felt that their students were coping well with online learning, and just over a quarter (27%) believed that their students were as engaged in online classes as they were during in-person classes before the pandemic.

The teachers in the survey also reported encountering barriers to teaching and learning, with more than half of the teachers reporting issues with having a stable internet connection, and about half or more reporting issues with accessing teaching supplies during the school year. About one-third said that they had trouble accessing a computer or tablet for teaching.

Almost all of the teachers, and even more of those teaching in hybrid or online, reported experiencing barriers involving their students, with the majority reporting issues at least a few times each week. About 90 percent of teachers reported having trouble helping students take responsibility for their work, keeping students engaged throughout the course, and getting them to complete daily or weekly assignments. Nearly 90 percent of the teachers noted that they struggled to get all of their students to complete the course.

Encountering barriers to teaching and learning may have an impact on teacher perceptions of student learning. More than half of the in-person teachers who felt that their students learned less than normal, reported encountering barriers with students. The relationship was even stronger for the hybrid/ online teachers.

Some of the most striking results focused on access to technology. The survey found that students who had access to a laptop, desktop computer or tablet, were much more likely to have positive perceptions of learning than to report that they learned less. The researchers also found a similar relationship regarding class-time activities involving technology or digital devices and positive perceptions. A majority of the in-person and hybrid/online students also showed positive relationships between their perceptions of learning and their self-reported respect of students who identify as a different race or ethnicity than their own.

In contrast to students, the relationship between teachers’ activities and their views of student learning were negative. Despite conducting a range of instructional activities similar in some ways to pre-pandemic times, and participating in a range of professional development, teachers still felt their students learned less than before the pandemic. The negative relationship between student learning outcomes and school activities was even more pronounced for those who taught in a hybrid/online mode.

“COVID-19 changed the lives of K–12 students and teachers,” Wang said. “They went through a totally intensified amount of worry and fear about the disease, about the impact on their family and finances, [and] on themselves, while the pandemic forced teachers and schools to suddenly incorporate online learning and teaching. Maybe we need to remind ourselves that we cannot expect in this kind of environment, for students to learn quite as much academically. We need to look beyond this and focus to implement the evidence-based interventions documented by What Works Clearinghouse [the initiative of the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences], in the coming years, while leveraging the improved technology skills students and teachers acquired to reclaim the lost learning opportunities and close down the gap.”

To read the full report, visit: https://cresst.org/publications/r870/