John V. Richardson, Jr. Honored by the Ohio Genealogical Society

UCLA Emeritus Professor of Information Studies John V. Richardson, Jr. has been recognized with the 2021 William H. & Benjamin Harrison Award from the Ohio Genealogical Society for his recent book, “Die Weber Familie: The Weber, Wollenschläger, Habermann, and Kempf Families in Early 19 Century Palatine Germany, Brazil, and the United States of America” (Los Angeles: ITA Press, 2020). The award is given by the OGS to honor the best Ohio-related family history and was presented to Professor Richardson during the Society’s premier Midwest genealogy virtual conference in April.

“Die Weber Familie” is the saga of Richardson’s paternal ancestors, the Weber family who left Neunkirchen am Potzberg, Bavaria in the early 19 Century. One branch of the family emigrated to Brazil – which was at the time, offering landowning incentives to immigrants to raise cattle – and the other branch began a new life in the United States, joining a German community in York County, Pennsylvania before settling in Morgan County, Ohio.

Professor Richardson, who prior to retiring from UCLA in 2013 taught a course on the use of genealogical resources, shares with Ampersand his journey of tracing ancestors through the push-pull theory of social, economic, and political forces the common threads among immigrant stories; and the draw of a really great potluck supper.

Ampersand: What inspired you to write “Die Weber Familie”?

John V. Richardson, Jr.: Growing up, I heard stories about my great grandmother from my father. He spoke a bit of German and my grandfather certainly must have, because his mother was German, a “Weber,” (vey-ber). So when I started teaching this class called an Introduction to Genealogical Resources, I thought it’s only fair that I’d be doing my own family history if I’m asking them to do their family history.

One thing led to another. I went to Germany, a couple of times visiting the heimat – the village where this family is from. They immigrated in 1833 and they’re the last of my ancestors to have emigrated. I got really interested because of the ethnicity issue where I grew up – Ohio was largely German-speaking in the 19th century, and it just presented some interesting things … the social, the technological, the economic, the political, and the ecological reasons. There’s a push-pull theory that talks about why people leave someplace. And then, you’re stuck with the question, ‘Okay, if we’re committed to leaving, where are we going to go?’ So that’s the pull factor?

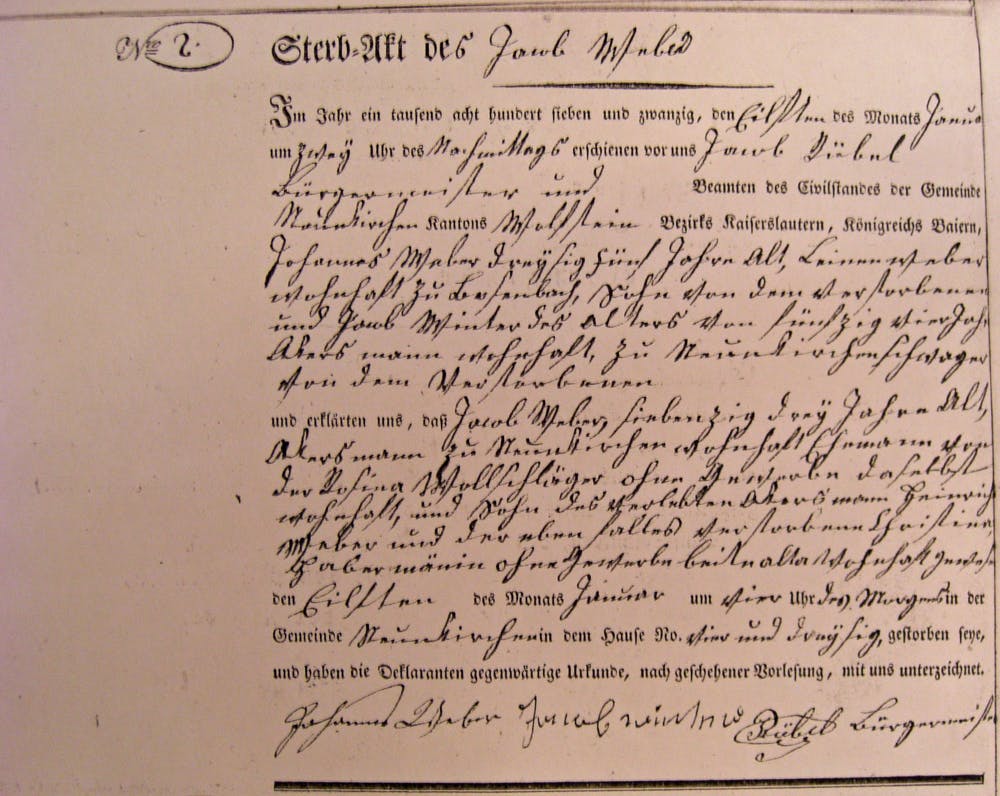

This family in particular is interesting because the older brother left five years earlier for Brazil. He wrote letters home and that’s become a whole big deal for the Brazilian branch of the Weber family. But my family stayed a little longer in Germany and when the paterfamilias died in 1827, those ties were loosened and finally in 1833 they decided to migrate across France to La Havre.

They landed in Baltimore and the Maryland German community isn’t very strong [there] but there’s a bigger one in Pennsylvania. And so, they take the road up to York County and settle there for about three years and then they make another push over into Ohio. That’s where I pick up the story, because I was born in Columbus.

The reason they changed their name from Weber to Weaver is that it sounds more American. So, it’s a story of assimilation or trying to assimilate because, finally, by the First World War, there was a very strong anti-German sentiment and speaking German wasn’t encouraged – there’s prejudice. Does this sound very familiar?

&: How did the German community form in Brazil?

Richardson: Let’s talk about the push and pull theory. There was already a German-speaking community down in Rio Grande do Sul. The pull for Brazil is that German immigrants were offered fairly generous land [for] cattle. You would be set up, so to speak. You received a reprieve on your taxes, so it looks like a pretty good deal. There are agents who are trying to recruit people to go and so, the older brother went.

His story is much more dramatic in terms of the crossing because the ship was demasted and they took on more passengers, and it became complicated. But the Germans are especially interested in it, because in his letters back to my family – the parents who were still living – he details what happened on board ship and then, his early years there in Brazil. But it still wasn’t enough to make them want to come.

I’ve seen photographs of the area in Brazil, it looks a lot like the wine growing countryside, the rolling hills. So, I could see why you might go. They did institute their own [religious] practices. In other words, I’m talking about their church. The older brother who went was not ordained, but he was religious enough that he was recognized as a community preacher. But at any rate, when when you look at Pennsylvania, or when you look at the area in Ohio where they settled, it looks a lot like the town that they left in Germany. So, in some ways they I think they must have felt very much at home.

I spent a fair amount of time looking at the push-pull. Going to Brazil [was] still an option. There’s an interesting newspaper article – it’s an argument between these two German-speaking Swiss whohave a long argument about the pros and cons of going to America and where in America you should go. I want to assume that my family must have heard – or read, rather – that dialogue.

They they were weavers, literally. It gets even better – the husband was the weaver but if you’re going to weave, what do you need? In Germany, it was wool, and so who did he marry? A Wollenschlager. That’s a person who pulls apart the wool, gets it ready so that it can be spun. I think that’s lovely that whatever she was to me – my great, great, great, grandmother – it was a Wollenschlager married to a Weber.

This is the very beginning of industrialization, and so the cottage industry doing this at home [in Germany] is in decline. And England is certainly getting cotton out of the [American] South, and so the prices for any woven materials are declining and so that’s pressure on the family: Do I really want to stay? What else could I do? How adventurous am I?

&: How were you able to piece this all together, along with the use of genealogical records?

Richardson: I’ve been working with the descendants – these cousins – I’ve had a lot of collaborators. If you and I are related, I would interview you and you shared the information that you had. Then, I built a very elaborate family tree. We’ve established [that] more than 1,000 people who have descended from this family, this adventurous family that left Germany the spring of 1833.

Family reunions, I know, were happening back in the 1920s. I didn’t exist yet, but my mom and dad went to those family reunions. Growing up, I must have gone[later. I don’t have recollections really – as a kid you know you’d go out and play in the churchyard with the other kids. But as I got older and then, as I said, with teaching that class in the UCLA Department of Information Studies, I got more interested because it’s a good case study.

Many of my students are trying to build their family trees are running into problems and so it was an interesting research problem: Can I trace these individuals? Can I prove their relationships and can I help understand immigration both emigrating – the exiting – and immigrating– the incoming?

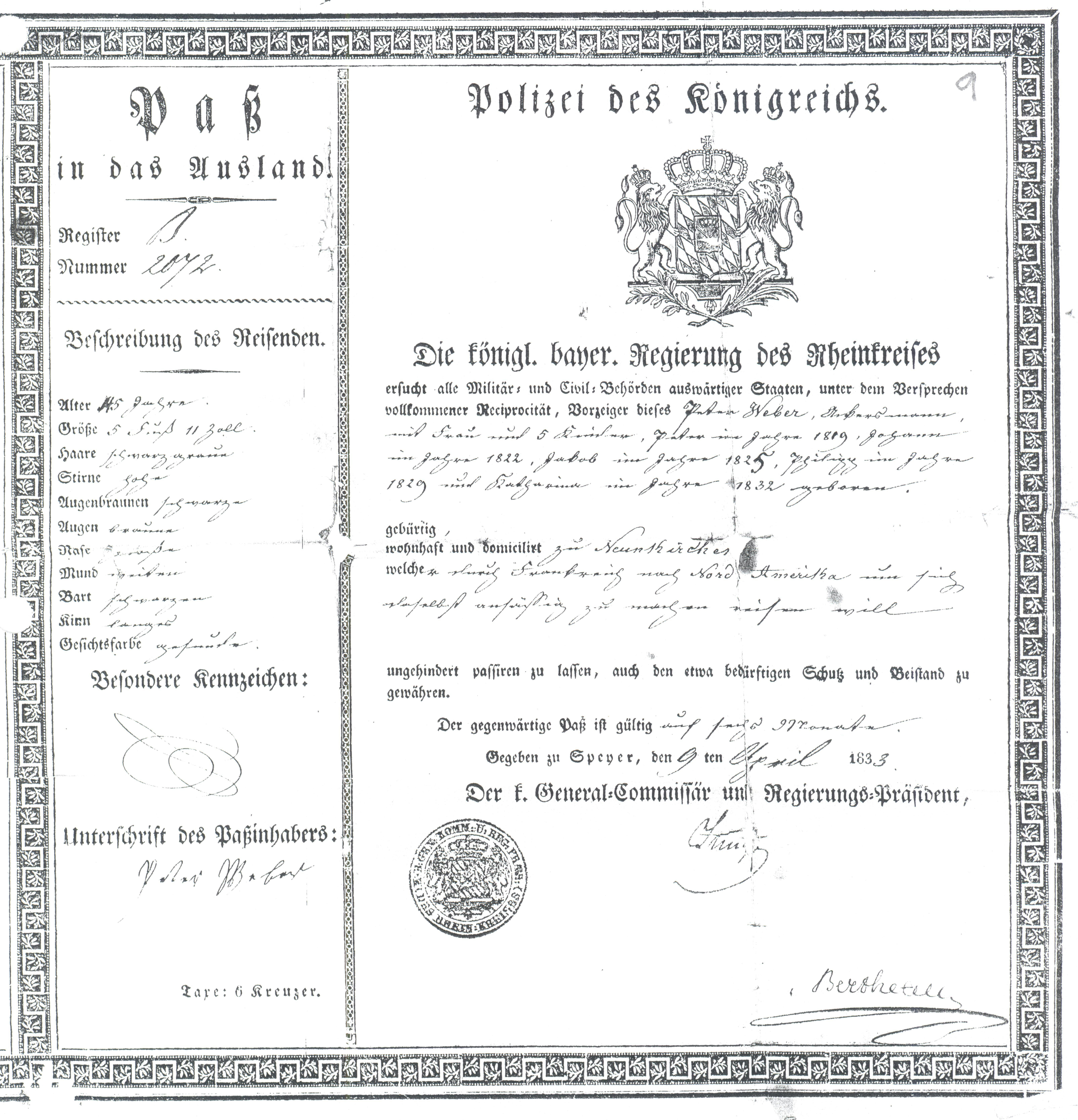

The family history is particularly interesting because the older brother, well, technically he left shall we say, in the middle of the night. He didn’t pay his taxes. There was an exit process, so once you declare your interest in leaving, you generally would receive a certificate from your community, from … the village official, saying that you’re in good standing and here’s a ticket of safe conduct so that you can depart and not be stopped at the various toll spots and be asked, ‘Where’s your paperwork?’ Does does this sound familiar?

The older brother was essentially undocumented, but it apparently didn’t seem to matter because, as I said, Brazil seemed to welcome his family. The brother that I descend from, came [to America] with ten individuals: the grandmother, his wife, and then his seven kids. On the immigration record, you can see the grandmother listed right next to a little baby, so I have this vision that the grandmother probably was holding the little kid as they came off the boat and went through immigration.

At one of the family reunions some years ago – I’m not exaggerating – I produced a 53-foot-long family tree. I wanted to put that up, so that people could go up to the chart and find themselves on the chart and then trace their way back up to the the progenitor of that family. So, it was pretty cool looking at the family tree and people would say, ‘Where am I?’ And I’d say, ‘Well, you’re going to be at the bottom, and the people who you’re descended from are going to be at the top, so let’s see if we can find you here on the bottom of the tree somewhere and then trace your line back up so you could understand.’

One of my favorite things that happened – there was this guy and I said to him, ‘So, you know how are you related?’ and he said, ‘You know what? I don’t know. My mom and dad always came to the family reunion, so I come.’

And so I said, ‘Well, tell me about yourself,’ and, of course, by then, laptops were a thing, so I have my laptop at the family reunion and I could build him into the tree. Finally, he figured out how he was related. But I thought that was so funny – that it’s just tradition, a custom that we go [to the reunion] … it’s a good potluck, there’s always great food.

&: While publicly-held records of marriage, births, and deaths can be found, how difficult was it to gain access to first-hand documents written by actual Webers?

Richardson: People have stories about what they’ve heard about their branch of the family, so a lot of it was oral history, trying to document it. And we did have a family historian who had preserved a lot of the early records. In my family’s case, it’s really extraordinary to see the so- called ‘passport.’ Many families, of course, had it, they did leave their little village with permission in good standing. But many families don’t actually have it, and so the younger brother’s line had preserved it, so it was really cool to see at least, photocopies of it.

I mentioned the letters that were being written home – that’s what was interesting. Rosina, the grandmother, took care of the correspondence and when she came to the United States, she brought those letters with her, so we have several pages of letters. When I started talking with German genealogists, they got all excited because that boat that went to Brazil was involved in two terrible storms and there was a lot of religious dissent on the different boats. It’s a complicated little story. But they got so excited because they said, ‘John, we know about the people who migrated to this community there in Brazil and we’ve heard stories about the boat but we’ve never had an eyewitness account. And the brother was writing back home, saying basically, ‘Hey Mom and Dad, I’m okay, but you won’t believe what happened on the way.’

&: What did the Ohio Genealogical Society find unique about “Die Weber Familie”?

Richardson: I had a framework for thinking about the push-pull aspect. It’s called the STEPE model, which means you look at the social, the technical, the ecological, the economic, the political things that are going on. That was my structure and apparently the Ohio Genealogical Society liked that a lot, enough to recognize it with the award. It’s nice to have validation.

&: Why do you think the topic of genealogy and the work that it takes to create a family history resonates so strongly today?

Richardson: Gardening is the most popular thing, and certainly during the pandemic, because you’re at home doing something around the house. But family history is also mentioned as being one of the most common activities right now. It means that there are a lot of people coming into… archives because where are you going to find a birth record, where are you going to find a marriage record… a death record? Public libraries in the United States usually have what are called local history collections, so librarians in public libraries, or archivists who work in a county historical society, need to understand the principles.

That would be one of the things in class I would talk about, what’s called the genealogical proof standard. How do I demonstrate that you and I are really related? It’s called kinship, and so we’re looking for evidence. How do we find that? Marriage records are really huge because … now I see there’s a kinship I can prove that this couple is married. How do you prove who you are? A driver’s license today, but in the 19th Century, we don’t have that. Every interaction that these ancestors [had] with some kind of governmental agency usually generates a record. Another one is naturalization – when you arrive in a foreign country do you want to become a citizen?

I talk a lot about the effort of the family to become citizens and what does it mean to give up – because when you become naturalized, as it’s called – your German identity. And I have a document where that’s exactly what it says, that my ancestor is wearing allegiance to the United States and no longer any allegiance to the King of Byron, [which was the nation of] Bavaria.

You think about the people south of our border – why are they coming? Because they don’t think it’s safe to stay in Nicaragua and El Salvador. I can imagine the same kind of stress back then in the southwestern part of what today we call Germany, because of course technically, Germany didn’t exist in 1833 it was a bunch of small little republics and duchies. The pressure to leave probably was taxation, impressment. If you’re not particularly militaristic, it doesn’t sound like a real good deal to have to sign on to the military.

Those [were] some of the pressures, the economic ones, the technological, as you know, the industrial revolution. I can empathize why they might think their lives could be better by coming to the United States. I think doing this, as it touches on so many things that are contemporary, unfortunately. It’s made me a lot more empathetic with more recent immigrants. We were pretty much all immigrants at some point or other.

Courtesy of John V. Richardson, Jr.