The Strategies of Resistance

An excerpt from Daniel G. Solórzano and Lindsay Pérez Huber’s book Racial Microaggressions: Using Critical Race Theory to Respond to Everyday Racism that analyzes how microaffirmations within Communities of Color reclaim the dignity and humanity that everyday racism takes away.

How Microaffirmation Empowers Communities of Color

Authors Daniel G. Solórzano and Lindsay Pérez Huber have theorized that racial microaffirmations have always been practiced as a response to racism and suppression. In their book Racial Microaggressions: Using Critical Race Theory to Respond to Everyday Racism, they assert that these affirmations of race have been conveyed in many forms—through art, performance, music, writing, spoken word, physical touch or simple facial expressions, all to counter daily inequities in a white-dominated society. Whether in public or private, there is mutual understanding through shared experience that creates an alliance and recognition in a way the authors write is an “everyday strategy of resistance.”

Excerpt

Everyday forms of affirmation and validation that People of Color engage in, the nods, smiles, embraces, use of language, and other actions that express acknowledgment, respect, and self-worth—are what we call racial microaffirmations.

Sociologist Michael Eric Dyson explains the historical significance of racial codes utilized by African Americans dating back to slavery. “In slavery, our fore bears had to devise a means of communication that slipped the notice of the majority culture, since what they had to say sometimes challenged the status quo … After slavery, the need for codes persisted because African Americans could not freely express themselves in “a hostile white world.” The nod became one of these codes. For Dyson, the nod is also a gendered code. He describes the act of acknowledgment and the recognition of humanity that we theorized in our understanding of a racial microaffirmation. In Dyson’s explanation, the nod is also a gendered act, specifically affirming Black men. Other Black scholars, however, discuss the nod in more general terms, as a culturally significant gesture practiced by Black communities, regardless of gender. For example, sociologist Elijah Anderson explains what he calls “the racial nod”:

“Being generally outnumbered by white people, black people feel a peculiar vulnerability, and they assume that other black people understand the challenges of this space in ways that white people cannot. Since the white space can turn hostile at any moment, the implicit promise of support black people sense from other black people serves as a defense, and it is part of the reason that black people acknowledge one another in this space, with the racial nod— an informal greeting serving as a trigger that activates black solidarity.”

Like Anderson, Black journalist Musa Okwonga reiterates the meaning of the nod to take on an element of unspoken community solidarity amid hostility. Okwonga states:

“The Nod is also so much more than that: It’s a swift yet intimate statement of ethnic solidarity—the closest thing to a secret handshake. Sometimes, though, it’s bittersweet, reflecting how far black people yet have to go to feel at home in their surroundings.”

Finally, African American Studies Professor James Jones examined how race is structured into the organization of the U.S. Congressional workplace. Among his findings was that Black staffers (men and women) utilized the nod as an adaptive strategy to feel seen in a white-male-dominated environment where they are often rendered unseen. In Jones’s study, the nod transcended professional rank, class, and age as a practice engaged by all levels of African Americans in Congress, from service employees to Congress members. It was used to facilitate introductions between Black people on Capitol Hill, to acknowledge “a shared experience” among them, and to gauge shared viewpoints and value systems.

Our research on the meaning of the nod practiced in African American communities solidified our initial cultural intuition that this gesture—found to be marked by a desire to build solidarity and empowerment within white space—prompted us to consider what kinds of racial microaffirmations we may encounter in our own Latina/o communities.

When thinking about racial microaffirmations, Lindsay Pérez Huber thinks about the moments spent with her daughters each year at their annual baile folklórico performances. “This tradition al Mexican dance performance has its roots in regional community dance forms in Mexico that were eventually adapted for stage performance. Each dance in the performance highlights the regional dance and music styles of the Mexican state from which it comes. This dance is always accompanied by music (and is even better with live music), and there are certain mariachi-genre songs that are very likely to be played at these performances. ‘Son de la Negra’ and ‘La Madrugada’ are almost always included in Mexican baile folklórico performances in the U.S. Southwest. Although I did not necessarily listen to these songs growing up in my household, hearing them—particularly as they are accompanied by Latina/o dancers, and especially children—has an effect on me. When I see them dressed in their bright, colorful dresses, dancing to music that celebrates Latina/o culture, it is a sight of beauty inspired by cultural pride. Each time (they have performed for many years) I get goosebumps. Music in our communities (and in others) can be a powerful form of racial microaffirmation. It can remind us of the beauty of the countries we are from, or the countries from where our elders/ancestors have come, of home. This has meaning particularly when you live in a place where your people are often demonized as criminals and economic burdens, and treated as second-class citizens.

“When I see and hear their dancing, I am reminded of the privilege I have to be able to engage in the (re)claiming of our culture and language with my daughters. From family stories passed down from my elders who lived in the U.S. Southwest for generations (Texas and California), I knew they constantly encountered racist nativist messages, particularly in schools—that Spanish was a ‘bad’ language, not allowed to be spoken, that being Mexican meant being less than, and that it was necessary to make strategic moves toward whiteness to avoid some of the harshest discrimination. My mother, aunt, and uncle all changed their names as elementary students at their predominately white Catholic school, when nuns couldn’t pronounce them, and their peers teased them. My grandparents did not speak Spanish to them, or to my sisters and me, as we later grew up with them. Today, I understand my family history and the choices they made to be mediated by racism and racist nativism. I also understand the consequences of this legacy of racist nativism. It has led to difficult moments in developing racial and cultural identities and an understanding and confidence in who I am and where I belong, and it has led to the linguistic terrorism I have experienced. However, as a parent, I could play a role in taking back some of what was taken from us. There have been many choices and efforts made to do this; dancing folklorico was one of them. Their dancing is a type of racial microaffirmation that is a response to the generations of racism experienced by my family in the U.S. Southwest.”

Daniel Solórzano explains how he first came to racial microaffirmations. “I’m reminded of my experiences growing up in neighborhoods to the east of downtown Los Angeles. My father, Manuel Solórzano Sr., inculcated in me a love of our communities. Not just the Latina/o communities of the eastside, but the African American communities of the southside, and the Asian-American communities of Little Tokyo and Chinatown near downtown Los Angeles. Riding with my father through these neighborhoods delivering Mexican bread to small markets infused a knowledge of these communities, a respect for these communities, a love of these communities. It was my first introduction to the cultural wealth that existed all through these communities. These journeys affirmed for me their beauty, their history, and my place within them. My later coming to ethnic studies generally, and Chicana/o and African American studies in particular, was further affirmation of my history and others’ histories—the stories

of People of Color. And now, as faculty, every year I attend Chicana/o Studies departmental graduations and Raza graduations. These culminating events are further affirmations for students, their families, their communities, and for us, their faculty.”

Racial microaffirmation is an everyday strategy of resistance. However, it is also something more. It is a particular form of resistance marked by the de sire to affirm the dignity and humanity of People of Color—those qualities significant to all human beings—but often denied by institutional racism and white supremacy. Racial microaffirmations, then, are a (re)claiming of the dignity and humanity that everyday racism attempts to take from Communities of Color. They can be seen all around us, in everyday environments, if we pay attention. For example, spaces created by and for People of Color can be a racial microaffirmation, such as the Raza. Racial microaffirmations can emerge in texts, be experienced through music and performance. The participants in our focus groups described other examples in art and pedagogy. A high school student once shared that learning about racial microaggressions gave her a way to “name” her pain. Microaffirmations can provide a language for People of Color to name their humanity.

Highlighted quote: “A high school student once shared that learning about racial microaggressions gave her a way to ‘name’ her pain.”

It is a concept that reminds us that our dignity is already within us, and that we affirm it every day with our families, in our communities, with colleagues, and with those whom we may not know, but with whom we share a “cultural intimacy” that binds us in our collective humanity. While this empirical research on racial microaffirmations has just begun, our research thus far has found that racial microaffirmations are already practiced in schools, communities, workplaces, homes, and many other spaces occupied by Communities of Color. If we were to look, we are sure racial microaffirmations could be found throughout history, in the struggles of People of Color for dignity and humanity in the face of racism. Put simply, racial microaffirmations are those everyday reminders that we matter—and we believe Communities of Color have been telling each other this, in their own ways, since the beginning.

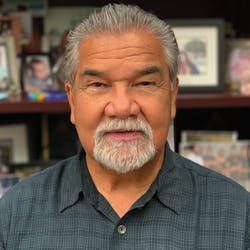

Daniel G. Solórzano, Ph.D., is the director of UC/ACCORD and a professor of social science and comparative education in the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies. He has written extensively on issues related to educational access and equity for underrepresented student populations in the United States, critical race theory, and racial microaggressions.

Dr. Lindsay Pérez Huber is associate professor in the Social and Cultural Analysis of Education (SCAE) master’s program in the College of Education at California State University, Long Beach. Her research uses interdisciplinary perspectives to analyze racial inequities in education, the structural causes of those inequities, and how they mediate educational trajectories and outcomes of students of color. She is also a Visiting Scholar at the UCLA Center for Critical Race Studies (CCRS).