Argentinean Ministry of Education Brings Teachers to UCLA

One hundred teachers, principals, and representatives from school districts and teacher education from throughout Argentina, arrived at UCLA on Sept. 26 for Programa de Becas para Docentes Argentinos en UCLA, a three-week conference to learn about best practices for urban schools in the United States. Activities included site visits to LAUSD campuses including UCLA Community School, UCLA Lab School, Ford Boulevard Elementary School, NOW Academy, Esperanza Elementary School, Mendez High School, Roosevelt High School, and Kingsley Elementary School. The groups also visited Emerson Middle School and University High School, which are in the UCLA TIE-INS Program.

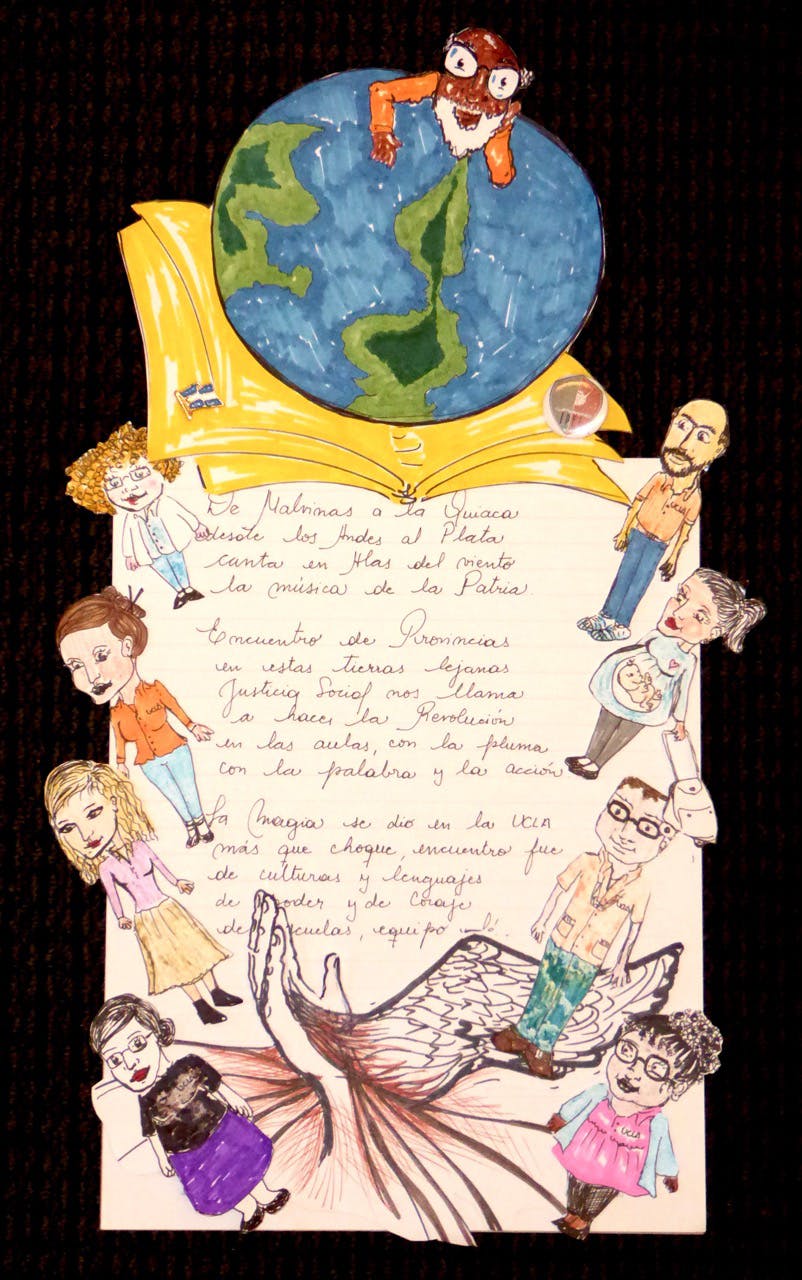

Professional development sessions tailored to the unique perspectives of teachers, principals, and teacher educators, addressed social justice education, inclusion, standards protocol, and the political context of education in Southern California. The first cohort wrapped up the Institute with an arts workshop at Self Help Graphics & Art in East L.A. A second cohort of 100 more teachers began their three-week session on Oct. 18. The Institutes are sponsored by Argentina’s Ministerio de Educación de la Nación, in collaboration with UCLA’s Center X and UCLA Ed & IS with the support of the Fulbright Commission.

Wasserman Dean Marcelo Suárez-Orozco welcomed the visiting teachers, school leaders, and administrators to UCLA, noting that, “To be part of an educated community is to do well and live well, for civic engagement, cultural belonging, citizenship, solidarity and the common good.”

Speakers included Wasserman Dean Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, Nancy Parachini, director of the Principal Leadership Institute at UCLA; Jo Ann Isken, PLI lecturer and field supervisor; Imelda Nava, Darlene Lee, and Jeff Share, faculty advisors in UCLA’s Teacher Education Program; and UCLA Professors of Education Megan Franke, Louis Gomez, Lorena Guillén, Tyrone Howard, and Pedro Noguera.

Parachini created the both three-week sessions of the Argentina Institutes with colleagues from Center X and its Teacher Education Program. She notes that the experience was one of shared learning between the Argentinian educators – who hailed from all 24 provinces – and LAUSD teachers, school leaders, and administrators.

“I learned about their love for their students and how they value their students above everything else,” she said. “They want the best for their students [and] they all had this incredible commitment and dedication to ensuring that everyone had a quality education.

“I also learned about their pride [in] what they can do to challenge the inequities that they see in their system, which was a common thread throughout the work that we did together,” Parachini said. “Even though [the inequities] might look different here than they do [in Argentina], we could relate to one another’s experiences. Their issues of marginalization and social justice are always framed around great economic differences. College is accessible to all but you have to get through elementary and secondary school to get there, so some of the students who might not come from a higher socioeconomic group may not have as much access. And they are dealing with language issues of the indigenous populations or the neighboring countries who are coming in to work in Argentina.”

Milagros Frias of Buenos Aires, teaches 1 and 2 grade, and is inspired by her mother who is also a primary level teacher.

“When I finished school I thought, ‘How can I help my country?’ and education is the thing that is most important, especially in our country,” Frias says. “I’m happy doing what I do. It’s not only mathematics and language. It’s also learning values and how to become good people [and] sharing my life with [students and families], and them with me. I can’t imagine doing anything else.”

Maria Eda of Neuquén in the province of Neuquén, also followed in the footsteps of her parents and extended family members.

“It’s a big family of teachers,” says Eda, who teaches computer science at the secondary and university levels and also trains teachers. “It’s like a tradition, but I choose it because I love it.”

TEP Faculty Advisor Jeff Share and several of his bilingual colleagues spent a full week with each cohort of visiting Formadores de Docentes (teacher educators), observing K-12 classrooms throughout LAUSD. The Argentinean teacher educators also joined Share’s student teachers as they visited and held a seminar at Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA), a community-based after-school program in Pico Union.

“The best part had to be when my students and the Argentineans had an opportunity to hear from each other and engage in conversations about notions of community and teaching,” he said. “My students spoke highly about how much they learned from our South American visitors. The Argentineans also told me about how impressed they were with our students and their openness to explore Los Angeles through an asset-based lens.”

“I was really encouraged by their words of wisdom and thoughtful questions,” wrote Marissa Cheung, a TEP student, in her reflection on the HOLA visit. “One of the [teachers] from Argentina shared how often we may become discouraged in our careers, but she encouraged us to continue growing as educators because we are bearing fruit even if we may not immediately see it and we have the opportunity every day to play a significant role in a student’s life. Even though we don’t speak the same native language, I felt connected to the educators from Argentina because of our shared passion.”

“It was great to hear [the Argentinean teacher educators] and what they had to say about what they have seen and heard from our discussions,” wrote Ana Ramos, a TEP student. “I felt so inspired and grateful to be able to hear from them about what it meant to be a teacher and what to keep in mind while we continue our journey to becoming teachers.”

Although the Institutes revealed commonalities between public education in Los Angeles and Argentina, there were several differences as well. Parachini said that the visiting educators were puzzled by the police presence in LAUSD schools, and Share noted that, “As under-funded as many of L.A.’s inner-city schools are, they still have more resources than most of the schools in Argentina.”

“They also pointed out their discomfort about the lack of play and social activities in many classes, especially in kindergarten and lower grades,” he said. “They felt that we are pushing the academics too early and not helping our students learn to socialize and explore through play. This is something that used to happen much more in the U.S. before neoliberal influences pushed those socio-emotional experiences out of the classroom in order to start with academics earlier. These comments by the Argentineans were helpful to remind me about the experiences our children are losing by being so focused on academics at such a young age.”

Teacher educators from Argentina and UCLA also had illuminating exchanges on their shared goals of preparing teachers. Eduardo Lopez, TEP faculty advisor, commented on the rigorous demands on teacher candidates and their educators.

“I was surprised that teachers in Argentina do not only work at one school but are traveling through multiple schools in different parts of the city – they often work at seven or eight schools,” he said. “Teachers are paid by the numbers of classes they teach and each school sets the amount to be paid. Their days often go from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. because of the traveling. Teacher educators also travel extensively and end their days very late as they support [teacher] candidates.”

“I was especially struck by the longer training and credential process,” said Lopez. “Where we certify a candidate in one year, they have four. While the longer process slows them to work more in depth in the formation, it also presents challenges. A particular challenge they face is that candidates will get frustrated or find another job and not complete the certification. Where we experience a loss of almost 50% of teachers during the first five years of full-time teaching, [in Argentina], they experience a similar loss of candidates during the four years of their formation.”

Lopez said that schools in Argentina and Los Angeles shared common struggles with similar contexts.

“The work with the Argentinians allowed me to reflect on my work with my teachers and how I could more intentionally develop their political identities,” he said. “We are both trying to understand how to prepare teachers to work effectively with poor immigrant communities. We are also trying to work against the neoliberal reforms of education. They have managed to retain a strong focus on play, creativity, the arts and cooperative learning. They also had a strong formation of the teacher as a moral, ethical and political educator.”

Share said that the visiting teachers and administrators were “extremely appreciative of this experience. Many of the visitors had never left Argentina and most had never been to the U.S. They were very grateful for this opportunity to hear and see so many different ideas about pedagogy, teaching, and learning. They also commented about how interactive most of the elementary classrooms were and how much they loved seeing students working collaboratively.”

Max Gomez of General Roca, Río Negro, teaches primary, high school, and university level students. He became a teacher “because I always knew that education is an institution that can help people with skills to make a better society.”

The challenges of building a better society – while addressing the challenges that exist in society – were examined by Professor Tyrone Howard, who spoke to the teachers. Providing data from his research on students of color and the school-to-prison pipeline in the U.S., Howard delineated the issues that American education has to overcome before expecting success in urban schools, including homelessness, high levels of poverty, children raised by individuals other than their parents, and the misguided sympathy of educators with low expectations of their students.

“I’m a product of Los Angeles schools,” noted Howard, who directs the Black Male Institute at UCLA. “I believe in public education. I fight for education – I especially fight for those who are the most vulnerable, because that was my upbringing. So much of what I do today is about remembering those communities, those families, those children… and trying to give them opportunity.

“There is a need to recognize the untapped potential in some of our poorest communities,” he said. “Our biggest challenge here is changing the minds of some of our educators to have them believe that poor children are capable learners. It’s important to listen to our students because they are trying to tell us about the challenges they face every single day. What I ask of my teachers is that they treat other people’s children with the same love, care, and attention that they would expect to be given to their own children.”

According to several of the visiting teachers, Argentinean educators share some of the same issues that Los Angeles educators face, including a high immigrant population, the challenges of mainstreaming special education students, and economic and educational disparities among indigenous populations. However, they said that homelessness is not an issue, and that they share more with their students and each other.

“We are more emotional,” said Frias. “We kiss, we hug. Also with the kids – I can’t imagine not hugging my students every day. We always say, ‘I love you’ or ‘I miss you. I teach about emotions. In our country, it’s good to cry, it’s good to be happy, it’s good to laugh.”

Eda asserted that the showing of emotions is a mutual benefit for both teachers and students.

“You share your life with your kids, so it’s necessary,” she said. “At my age, I have a lot of experience, so my work is to share [it] with young people.”

“One of the phrases they taught me was “calor humano” – human warmth and kindness,” said Parachini. “You can see they expressed that in their groups here when they were working together. They really had a lot of love and respect for each other and admiration for one another’s work.”

“The conversations were always so enriching and passionate,” said Share. “Their passion was probably the most inspiring aspect of the experience for me. Everywhere we went, they were so excited and interested in learning and sharing.”

Fabiana Agnes of Rio Grande, Tierra del Fuego, teaches a range of students from kindergarten level to new and aspiring teachers.

“When you teach with heart… you see the student, what happens in their life,” she said. “You have to know different things in the school – its climate, the social and economic context of the students. Teachers ask me all the time, “What happens to these students?” And I ask them, “What do you do with them? Talk to your students. Look at your students and their histories.”

For a statement on Programa de Becas para Docentes Argentinos en UCLA by Andrea Carolina Cifuentes Fernandez, click here.

For a video of the 2017 Programa de Becas para Docentes Argentinos en UCLA, click here.

Photo by Todd Cheney, UCLA